Writer: Jordan Jones

Essay Mentor: Renee Gladman

This essay was produced in conjunction with the exhibition worried notes by Keli Safia Maksud, with mentorship from Abigail DeVille and on view at CUE Art Foundation from January 25 – March 16, 2024. The text was commissioned as part of CUE’s Art Critic Mentorship Program, and is included in the free exhibition catalogue available at CUE and online.

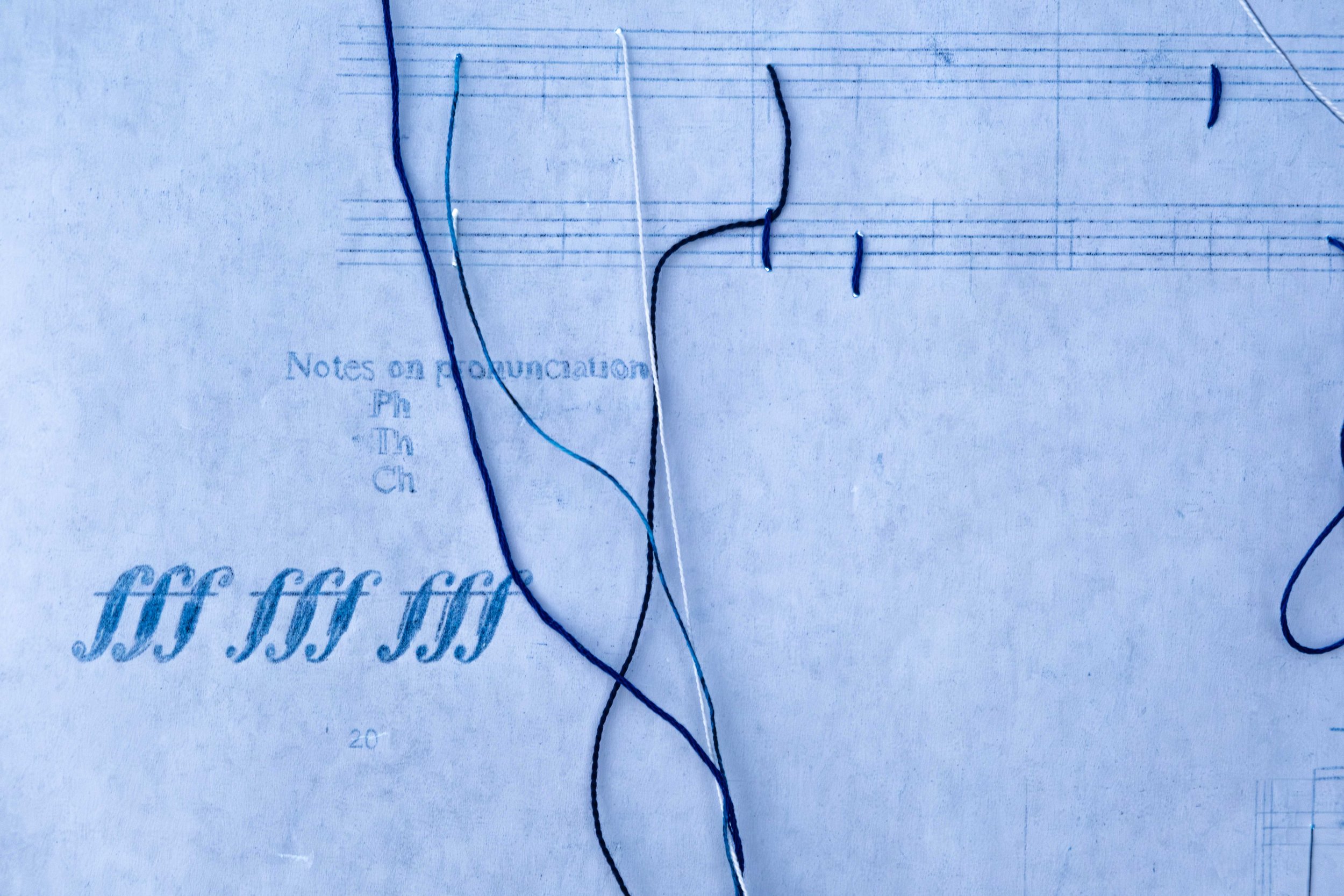

Detail of how then do you position yourself?, 2023. Photo by Leo Ng.

Keli Safia Maksud presents us with worried notes. Musically, a worried note, or a blue note, is a pitch that destabilizes the major scale—a sound between a note on the major scale and a note on the blues scale.¹ Introducing a worried note unsettles the path of a song, progressing it in a way one might not expect. Worry also unsettles the paths of a thought; rather than progressing it forward, it sits and dives deeper and deeper. Maksud’s practice lives between these two meanings. She imagines a process of worrying that is not just an extension of anxiety, but also one that is a furrowing investigation. Worrying as adopting an ongoing concern. Worrying as aligned with dis-ease. Worrying as the act of upsetting accepted structures and ideas. In worried notes, Maksud interrogates the languages of musical scores for African national anthems, architectural diagrams, and colonial cartography. She worries them. She takes unquestioned symbols and examines their self-evidence, asking, with fierce insistence: “But why?” Turning up shrugs from traditional knowledge sources, Maksud instead turns to more embodied ways of knowledge-making. Worrying meets the hand, and drawing becomes a means of wayfinding, of navigating through these concerns.

Discussing her interest in forensic etymology, scholar Christina Sharpe shares, “I just get obsessed about certain things and I just want to keep staying with it and worrying it and worrying it and worrying it.”² Maksud’s practice aligns with Sharpe’s in this way. Worry becomes a durational activity—a slow peeling back of meaning. It turns into a scholarly strategy, a form of dedicated study. Sharpe continues, “I can return to the same thing again and again and again and again because I’m trying to see it from all of these different angles and trying to understand something about it…I just think that staying with something can open up a different kind of aperture by which we don’t collapse everything into it, but by which we can make an argument or see the world.”³

The long scrolls of Maksud’s work are dotted with such apertures. They are evidence of her worrying—and of her shaping of a particular way of looking. These apertures appear sometimes as the head of a note, a fermata; other times as an asterisk, a dark star. Worry a piece of paper—worry it further—and a hole appears, through which a needle might be pulled. Where Maksud sees a dashed line, she also perceives a sewn line—a series of punctures. Perhaps worrying suggests a need for openings. The holes she creates encourage viewers to also worry the work—to view it from many perspectives.

Two works in the gallery, if I say the sky’s small arithmetic, its inscription, its echo and (our) making / unmaking / making / unmaking (2023) are presented on freestanding metal armatures, angled toward each other in the center of the space. It is easy to circle the works, to move back and forth between the dense blue expanses and the navy notations on white ground; between neat, stitched lines and loose, drooping, tangled threads. A staid text becomes permeable—a double-sided thing that is worried from many angles. There is no true front and back to each work, only the side we encounter first and the side we encounter second, each complicating the other. Instead of prompting us to look head on, Maksud encourages us to adopt an askance and roving viewpoint. Standing perpendicular to the work, you can begin to grasp both sides; moving around it, you can begin to discern the details.

Installation view of worried notes, 2024. Photo by Leo Ng.

Created from carbon paper, a tool used in drafting, Maksud’s drawings are situated in the middle of a process—unfixed, open to edits, but full of possibility. She is not afraid to linger in a place of unknowing. She describes her process as, “denoting things that you haven’t encountered yet, but knowing that you will.”⁴ In bits and pieces, with time in necessary darkness, the drawings find real world analogs. Thelonious Monk plays, and for Maksud, it happens like this:

I was listening to something of his and I understood it in my drawing. I don’t read music, so most of the time, I am drawing in the dark, placing one symbol next to another—putting them in some sort of affective proximity to one another, creating new connections and layers of meaning. But as I listened to Monk, I could see the lines or notes that I produced on the blue side of the paper. They aren’t straight lines that run up and down a staff, but instead notes that cut across, creating new pathways.⁵

Maksud is not concerned with learning how to read sheet music through the traditional avenues. In lieu of reading—and driven by a curiosity grounded in the systems of symbols themselves—she draws. She is drawing her way toward these moments of encounter, of knowing, where a line becomes sound, where a draft becomes something briefly definitive and tangible. Scoring as mark making. Mark making as meaning making. “I think that drawing is the way that knowledge has been produced,” she asserts. “A map is drawn. Writing is drawing letters. You draw music on paper. You draw architectural plans. Drawing has always been the element of all these other disciplines. Drawing enacts an architecture, a built environment that organizes bodies and governs how we move through space.”⁶

For Maksud, drawing both creates and enacts knowledge; it is a political act. A score becomes music. A map becomes the land. These lines become the boundaries we find ourselves placed within or without. Situating her work inside the carbon copy, she reopens previously foreclosed upon space to new possibilities, continued learning, and future revisions.

Detail of if I say the sky’s small arithmetic, its inscription, its echo, 2023. Photo by Leo Ng.

Placed on the floor throughout the gallery are three monitors that comprise ttttaappp (2024). This work draws upon footage pulled from a wide array of sources: performances of Thelonious Monk, Zaouli dancers, Jimmy Slyde, and children from a military school in Nigeria. Each of the three channels depicts a film that is cropped in close on the feet of performers who are tapping along to unheard music. ttttaappp rhythmically flips through footage of these performers, lighting up with bursts of movement and then switching to a black screen.

Detail of ttttaappp, 2024. Photo by Leo Ng.

While the feet are silent, Maksud’s sound work, untitled bpm(s) (2024), introduces the tapping of metronomes that periodically punctuate the space. A metronome is a device designed to keep time. Within a score, the symbol ( 𝄒 ) is used to tell the musician when to take a breath. Rest marks indicate when and for how long to pause. The time signature “4/4” designates that the music is to be performed in what is known as “common time.” There are many external structures used to regulate the performer. ttttaappp, however, reminds us that the body keeps its own time—that it has its own bpm. Looking closely, the performers in the films don’t simply tap their toes up and down, but rather employ a rich and varied language of movement. They slide and shuffle. They kick up the earth. The tapping is not isolated to the foot; it is an extension of the whole body. They have personality—playful or strict, free, insistent—that drives forward an unheard beat.

Scores, maps, and diagrams can be understood as works of capture—the capture of a sound before it leaves the air and escapes one’s memory; the occupation of land; the control of space. ttttaappp undoes the work of this capture. It centers the performers rather than the score, and allows us to witness their feet scoring their own ephemeral compositions. We can’t hear them, but they are felt. Low to the ground and close to our own feet, rather than traveling through the language of symbols, their rhythms can circulate from body to body.

Detail of (our) making / unmaking / making / unmaking, 2023. Photo by Leo Ng.

The national anthems that initially informed Maksud’s scores have become just a starting point. Maksud has turned down the volume on these songs to listen to something deeper playing across them. She describes it like this:

The sound of a national anthem for me is very up—it’s being projected down onto the people—so my work has also been about trying to understand what’s happening below, and the complexity of what might be below. A very deep, low…[frequency] can also have a complexity within it that we have to attune ourselves to listen to in a very different way.⁷

Maksud pushes beyond and below the music—attending to the lower frequencies. The scores shake loose the defined space of the national anthem and become something else. In removing the blast of sound typically produced by the performance of an anthem, they become something you can get up close to. Moving through the gallery, the faint lines and symbols present throughout the work require a keen eye and an even sharper ear. Here, the dynamic markings are piano or pianissimo even. The scores are not merely quiet, but played softly—sounding with a specific texture and pressure. Look and listen closely, and something else comes through:

cresc. e pesando

con bravura

TERRITORY

a Tempo

THE CAPE COLONY

Chants Africains

Un poco piu mosso

Plan de Léopoldville

Andante quasi fantasia

Congo Belge

sur chaque tem de la mesure

COLONY & PROTECTORATE

While national anthems are expressed loudly and publicly, Maksud wants us to be aware of what is internal and quiet within them. She heeds Tina Campt’s warning that, “contrary to what might seem common sense, quiet must not be conflated with silence. Quiet registers sonically, as a level of intensity that requires focused attention.”⁸ Writer Kevin Quashie offers further counsel, stating, “Quiet is uncertain and it is sure; trembling and arrogant. Quiet is faith in that it can embrace what there is little evidence of. Quiet can exist without horizon, and it has no consecutive. Quiet is like the moon, rarely showing its full wondrous sphere and instead offering slivers of its potent, tide-shifting self. Quiet is to feel deeply and to feel what is deep.”⁹

Detail of (our) making / unmaking / making / unmaking, 2023. Photo by Leo Ng.

Within the gallery, rather than creating enclosures with suspended scrolls, Maksud has made a series of passages. They create their own loose architecture. They are not rigid barriers, but rather suggestions for space. worried notes offers a set of plans in progress. “Plans for what?” I ask. “What is it building in space?” Maksud answers. “It is a kind of wayfinding. It is like a wayfinding system for me to something—for something—that I am not quite sure what I am looking for. That’s fine.”ᴵᴼ

Maksud’s latest focus is the stars. They appear in more places than you’d think. They are in sheet music, on the flags of nations, and on maps to mark points of interest. If you catch the work from just the right angle, the deep blue is, in fact, scattered with constellations of light. Maksud’s punctures, apertures, and openings have yet another purpose. Stars in the night sky have long been used as tools for navigation. A crescendo mark is just an arrow pointing one in a particular direction. The structures Maksud has built help chart a course. how then do you position yourself? (2024) becomes another kind of compass, with four scores oriented along a set of axes. Until we get where Maksud is guiding us, I am happy to follow: to worry the signs and symbols, to sit in a dark blue space, to listen to the quiet, and maybe even to tap along.

Detail of if I say the sky’s small arithmetic, its inscription, its echo, 2023. Photo by Leo Ng.

Endnotes

[1] Ethan Hein, “Blue notes and other microtones,” The Ethan Hein Blog, May 5, 2010. [https://www.ethanhein.com/wp/2010/blue-notes]

Aria Dean, “Worry the Image,” Art in America, May 26, 2017. [https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/features/worry-the-image-63266]

[2] David Naimon, “Between the Covers: Christina Sharpe Interview,” Tin House, accessed January 15, 2024. [https://tinhouse.com/transcript/between-the-covers-christina-sharpe-interview]

[3] David Naimon, “Between the Covers: Christina Sharpe Interview.”

[4] Interview with Keli Safia Maksud, Brooklyn, NY, November 19, 2023.

[5] Interview with Keli Safia Maksud.

[6] Interview with Keli Safia Maksud.

[7] Interview with Keli Safia Maksud.

[8] Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images (Press Durham and London: Duke University, 2017), pg. 6.

[9] Kevin Quashie, The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture (New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2012), pg. 134.

[10] Interview with Keli Safia Maksud.

About the Writer

Jordan Jones is an arts worker living and working in New York. She is currently the Exhibitions Coordinator at Independent Curators International (ICI). She has participated in the Interdisciplinary Art and Theory Program (IATP), the Studio Museum in Harlem’s Museum Education Practicum, and the Center for Book Arts’ Creative Publishing Seminar for Emerging Writers. She has also completed residencies at the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council’s Arts Center on Governors Island and The Vermont Studio Center. Jones received a B.A. from Williams College.

About the Writing Mentor

Renee Gladman served as the mentor for this essay. Gladman is a writer and artist preoccupied with crossings, thresholds, and geographies as they play out at the intersections of poetry, prose, drawing, and architecture. She is the author of fourteen published works, including a cycle of novels about the city-state Ravicka and its inhabitants, the Ravickians—Event Factory (2010), The Ravickians (2011), Ana Patova Crosses a Bridge (2013), and Houses of Ravicka (2017)—as well as three collections of drawings: Prose Architectures (2017), One Long Black Sentence, a series of white ink drawings on black paper, indexed by Fred Moten (2020), and Plans for Sentences (2022). Recent essays and visual work have appeared in POETRY Magazine, The Paris Review, Gulf Coast, Granta, Harper's, BOMB Magazine, e-flux, and n+1. She has been awarded fellowships, artist grants, and residencies from the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard, Foundation for Contemporary Arts, the Lannan Foundation, and KW Institute for Contemporary Art (Berlin), and is a 2021 Windham-Campbell Prize winner in fiction.

About the Art Critic Mentorship Program

This text was written as part of the Art Critic Mentorship Program, a partnership between CUE and the AICA-USA (the US section of International Association of Art Critics). The program pairs emerging writers with art critic mentors to produce original essays about the work of artists exhibiting at CUE. Learn more about the program here. No part of this essay may be reproduced without prior written consent from the author.